Martha Comes to Visit

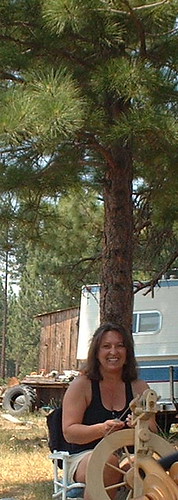

If asked what I do, I usually say I am a weaver, but that is misleading.

Weaving, for many people, is choosing a goal (dishtowels, say, or a new jacket), picking a yarn off the shelf, deciding on a weave structure and how to sett the yarns, how long and wide the fabric needs to be, and then proceeding to set those parameters up and warp the loom.

But when I start a project, I usually start with dyeing. I often also start with spinning, and both of these aspects of what I do are more time consuming, and more engaging, than the weaving itself.

I want the color that I am imagining in front of my eyes. I weave to get the fabric off the loom, to handle it, to see if all the pieces have fallen into place.

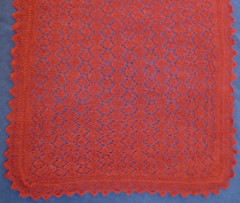

I have learned my favorite weave structure (plain weave) well. Oddly, there are lots of ways to weave plain weave: balanced, warp faced, weft faced, warp dominant, weft dominant, fine warps and thin wefts of thick wefts, heavier warps with fine wefts or thick ones, or alternately fine and thick threads in either direction. I play with all of these factors, and yet it is still everyday plain weave.

I weave simple peasant cloth, which I have mentioned before, and which I consider a compliment. I define peasant cloth as good, sturdy well woven cloth, meant to last and hold up through wear and use. No delicate flowers for me.

I have been weaving for over 30 years, and am to the point in my weaving career that I am reasonably certain to achieve the fabric I plan. There are surprises, of course, which keeps the whole thing interesting. But the structure of the fabric is not what I think about.

It is tactile and visual pleasure, the spinning, dyeing and weaving off lengths of colorful fabric.

Color elicits the first response from most everyone, good or bad. It is the first thing we see in looking at clothing, say, or dishtowels. Closer inspection, when we handle the cloth, gives us a feel for the hand of the fabric, smooth, supple, slippery, fuzzy, soft, harsh, whatever. And then last, if we have a weaver's perspective of cloth, we look at the structure of the cloth.

Many weavers spend the bulk of their weaving time planning the structure, thinking of ways to manipulate the threads in the warp and weft to create a fabric that has structural interest. Somehow, I missed that gene. I think it goes along with the counting gene, because sometimes I get that counting stuff all wrong too. But I am resourceful, I can adjust: with plain weave, a few extra threads here or few less there are not a crisis. Many weave structures require a specific set of threads, and the right number of threads, and that counting gene is necessary.

Madelyn van der Hoogt, weaving teacher and currently editor of Handwoven magazine, has long held that there are two types of weavers: the Structure-Pattern people, and the Color-Texture people. I, obviously, fall firmly into the latter camp. We all cross over to greater or lesser extent, and occasionally I have been known to weave off a piece of fabric with color and structure. Those fabrics are notable and rare though, and a cause for comment among people who know me.

It is similar in knitting: there are the color-stranders, the texture knitters, and the lace knitters. Texture knitters and lace knitters seem very similar to me: some create bumps and some create holes, but they are manipulating the needles and yarn in their dance of choice. There are probably intarsia knitters too, but I don't know any of them.

There is no right or wrong here. People fall into either (or some of both) camp of weavers and knitters. Some people have an attitude about all of this, and would like to make their camp the only camp, or the most important camp.

In weaving, many people feel the need to get bigger and more complex equipment just to become a real weaver. But small looms, simple equipment, and hand manipulated weaves have a pleasure and tactile joy some of the quasi-industrial looms do not. Hours spent in quiet spinning, lifting each thread step by step over and over in a pickup pattern, can be balm to sooth the restless soul.

I so enjoying spinning and dyeing my yarns. Much of the pleasure of all of this fabric stuff would be lost, for me, without those two aspects.

Martha? Flowers:

Sent by my son and his wife, from MarthaStewartflowers.com. They are beautiful, and open more each day.

And the color delights me.

Weaving, for many people, is choosing a goal (dishtowels, say, or a new jacket), picking a yarn off the shelf, deciding on a weave structure and how to sett the yarns, how long and wide the fabric needs to be, and then proceeding to set those parameters up and warp the loom.

But when I start a project, I usually start with dyeing. I often also start with spinning, and both of these aspects of what I do are more time consuming, and more engaging, than the weaving itself.

I want the color that I am imagining in front of my eyes. I weave to get the fabric off the loom, to handle it, to see if all the pieces have fallen into place.

I have learned my favorite weave structure (plain weave) well. Oddly, there are lots of ways to weave plain weave: balanced, warp faced, weft faced, warp dominant, weft dominant, fine warps and thin wefts of thick wefts, heavier warps with fine wefts or thick ones, or alternately fine and thick threads in either direction. I play with all of these factors, and yet it is still everyday plain weave.

I weave simple peasant cloth, which I have mentioned before, and which I consider a compliment. I define peasant cloth as good, sturdy well woven cloth, meant to last and hold up through wear and use. No delicate flowers for me.

I have been weaving for over 30 years, and am to the point in my weaving career that I am reasonably certain to achieve the fabric I plan. There are surprises, of course, which keeps the whole thing interesting. But the structure of the fabric is not what I think about.

It is tactile and visual pleasure, the spinning, dyeing and weaving off lengths of colorful fabric.

Color elicits the first response from most everyone, good or bad. It is the first thing we see in looking at clothing, say, or dishtowels. Closer inspection, when we handle the cloth, gives us a feel for the hand of the fabric, smooth, supple, slippery, fuzzy, soft, harsh, whatever. And then last, if we have a weaver's perspective of cloth, we look at the structure of the cloth.

Many weavers spend the bulk of their weaving time planning the structure, thinking of ways to manipulate the threads in the warp and weft to create a fabric that has structural interest. Somehow, I missed that gene. I think it goes along with the counting gene, because sometimes I get that counting stuff all wrong too. But I am resourceful, I can adjust: with plain weave, a few extra threads here or few less there are not a crisis. Many weave structures require a specific set of threads, and the right number of threads, and that counting gene is necessary.

Madelyn van der Hoogt, weaving teacher and currently editor of Handwoven magazine, has long held that there are two types of weavers: the Structure-Pattern people, and the Color-Texture people. I, obviously, fall firmly into the latter camp. We all cross over to greater or lesser extent, and occasionally I have been known to weave off a piece of fabric with color and structure. Those fabrics are notable and rare though, and a cause for comment among people who know me.

It is similar in knitting: there are the color-stranders, the texture knitters, and the lace knitters. Texture knitters and lace knitters seem very similar to me: some create bumps and some create holes, but they are manipulating the needles and yarn in their dance of choice. There are probably intarsia knitters too, but I don't know any of them.

There is no right or wrong here. People fall into either (or some of both) camp of weavers and knitters. Some people have an attitude about all of this, and would like to make their camp the only camp, or the most important camp.

In weaving, many people feel the need to get bigger and more complex equipment just to become a real weaver. But small looms, simple equipment, and hand manipulated weaves have a pleasure and tactile joy some of the quasi-industrial looms do not. Hours spent in quiet spinning, lifting each thread step by step over and over in a pickup pattern, can be balm to sooth the restless soul.

I so enjoying spinning and dyeing my yarns. Much of the pleasure of all of this fabric stuff would be lost, for me, without those two aspects.

Martha? Flowers:

Sent by my son and his wife, from MarthaStewartflowers.com. They are beautiful, and open more each day.

And the color delights me.